Five people were elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame on Sunday night, and Dick Allen wasn’t one of them.

This probably would have surprised Allen, for whom rejection was a constant theme in his career, least of all.

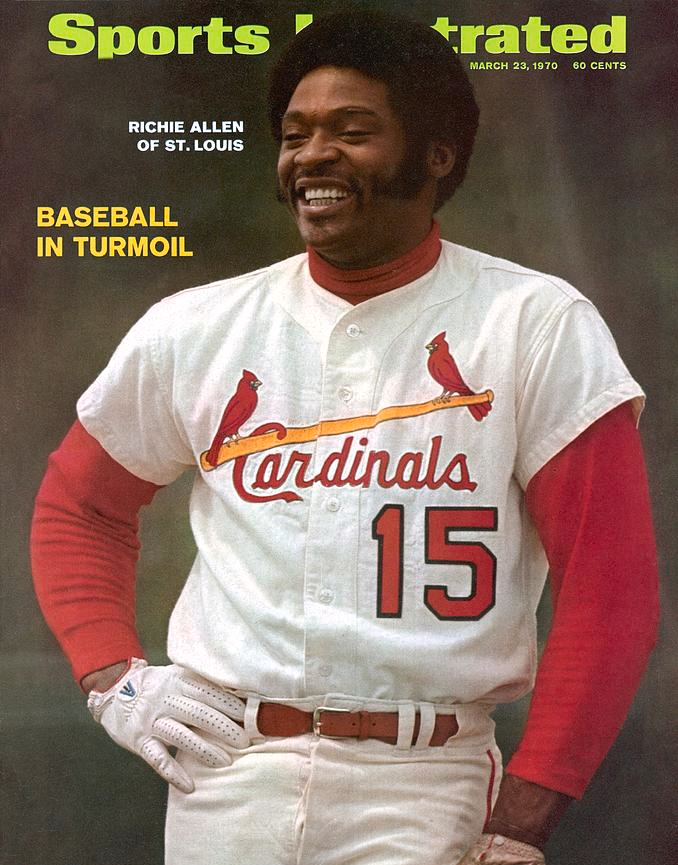

Allen hit 32 home runs in 1969, 34 in 1970 and 23 in 1971. He averaged nearly 30 homers a year in those three seasons and was traded after each of them. The Phillies, Cardinals and Dodgers shed themselves of Allen as quickly as a Congressperson dumping stock before the pandemic.

It’s hard to imagine there’s ever been another player who hit as many home runs in a three-year span who was deemed so expendable.

Allen missed the Hall on Sunday by one vote, for the second time. Folks on one side of the political aisle thought they might never miss a Jim Bunning vote, given his record in Congress. Liberal Phillies fans missed him on Sunday. Bunning, who was on the Golden Era Committee in 2014 when Allen first fell one vote short, died in 2017 and couldn’t give Allen the final vote he needed.

Who’s voted in and who’s left out has been controversial ever since the Hall of Fame started keeping score in 1936. In 1938, the third class was just one member, pitcher Pete Alexander, though 120 players received votes. The top 23 vote getters of 1938, 29 of the top 30 and 54 in all have since been inducted, a pretty good indication that neither the voters nor the process has ever been perfect.

Red Dooin, a catcher in the first two decades of the last century with a .240/272/298 triple slash, no doubt had his hopes raised by the vote he received in 1938 (it was his last; he got one other in 1937. Perhaps his champion lost the vote).

There are competing visions of what the Hall should be as surely as there are players competing to get in. Glee won Sunday’s vote over substance.

Among five candidates, the Hall of Fame added Buck O’Neil, baseball bon vivant; Gil Hodges, first baseman on the sport’s most-chronicled team if not its best, and manager of perhaps its most wondrous; and Jim Kaat, among the sport’s most enduring pitchers whose playing career spanned seven presidential administrations, from Eisenhower to Reagan. It also added the groundbreaking Minnie Minoso and unlucky Tony Oliva in a class that drew mostly plaudits but for Allen.

O’Neil was, by contemporary accounts and incomplete stats, a decent player in the Negro Leagues, but that’s not what earned him election. He was the first Black coach in MLB and a longtime scout who saved the career of Hall of Famer Billy Williams. He was the star of Ken Burns’ series on the sport and the subject of a wonderful Joe Posnanski book.

To paraphrase a tweet from before the vote, You can’t tell the story of baseball without telling the story of Buck O’Neil, and if you think part of the mission of the Hall is to do that, you welcome O’Neil. And as Charles Pierce tweeted Sunday, O’Neil’s election, “Classes up the old joint immeasurably.”

(But what about John Donaldson, one of the greatest of Black pitchers from before the creation of the Negro Leagues, whose story has rarely been told? Should he be excluded because he wasn’t around to do the late-night talk show circuit? Unfortunately, for now he was.)

Minnie Minoso got in, and I’m good with that, too. Minoso was the first Black Latin player after segregation ended and “for an 11-year run … he was the second-best player in the American League,” according to fangraphs.com’s Jay Jaffe in a 2020 interview with ESPN. Minoso was in the top five of the MVP vote four times, and easily could have won it in 1954, his best season (.320/411/535). He was a hit away from a .300 lifetime average, he stole 216 bases, had nine .300 seasons, was hit by 195 pitches and won Gold Gloves three of the first four years they were awarded. That trumps the six times he led the AL in caught stealings (he led it in HBPs 10 times).

If part of the mission of the Hall is to acknowledge the shortcomings in the game’s history, you welcome Minoso, who may well be deserving on his play alone.

After that, it became more of a popularity contest of the kind Allen never did well in.

Tony Oliva, a lifetime .300 hitter who played but 11-and-a-half seasons, got in. Were there a Hall for the Might Have Been, Oliva would be a first ballot inductee (along with Don Mattingly, Johan Santana, and fill in your favorites). Knee injuries did to Oliva’s career what pitchers couldn’t — they curtailed it.

Oliva was a three-time batting champ who had six .300 seasons; Allen was a three-time slugging champ who hit 131 more career homers, stole 47 more bases and had an OPS 82 points better. And had six .300 seasons and half of a seventh.

Jim Kaat debuted in the majors in 1959 and has been around, in one capacity or another, ever since. He won 25 games in 1966 and 283 in all and was an outstanding fielder. But he pitched for 25 seasons and received Cy Young votes in only one of them. Don Sutton probably looked at Kaat and saw a compiler.

The voters looked at Kaat, made longevity more of a criteria than it deserved to be, added it to the goodwill accumulated over 63 seasons and put him in the Hall. Ted Williams said in his induction speech, “I received two hundred and eighty-odd votes from the writers. I know I didn’t have two hundred and eighty-odd close friends among the writers,” but fraternity might have helped Kaat more than it did Williams, who didn’t need it. Or Allen, who wasn’t the fraternizing type.

(Most of Kaat’s post-playing career has been as a genial broadcaster, without incident. Last fall, though, he said a team should “get a 40-acre field full of them” when talking about Yoan Moncada. One can draw their own conclusions about how much the committee weighed the racism Allen faced in his career in Kaat getting elected and Allen not. Kaat apologized a few innings later.)

And then there’s Gil Hodges, who wasn’t good enough as a player (370 homers, .273 average, 43.9 WAR) to get into the Hall and wasn’t good enough as a manager to get in (ample credit to Hodges for the 1969 Miracle Mets, but in the next two seasons the Mets were 83-79 and 83-79, and in total he was 93 games under .500). Finally, the whole was greater than the sum of its parts. Hodges was the fifth Brooklyn Dodger of Roger Kahn’s Boys of Summer to go into the Hall, which might be evidence the book was even better than the team it extolled. Nostalgia is a powerful drug.

All of the selections are defensible, and all have merit. None sinks to the depths of Harold Baines’ election, which was to Hall of Fame votes what Neville Chamberlain’s 1938 Munich Agreement was to peacekeeping.

But whatever one’s vision of what the Hall should be, honoring its best players should be foremost.

Dick Allen is one of the handful of best hitters in the game’s history. He ranks 22nd all-time in OPS+, and of the 21 players who bettered Allen’s 156, three played in the Negro Leagues and three more in the 19th century. Since 1900, only 15 major-leaguers have had a better OPS+ than Allen, and those whose OPS+s were worse include whole rooms at Cooperstown or plaques to come — Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Mel Ott, Joe DiMaggio, Manny Ramirez, Frank Robinson, Willie McCovey, Miguel Cabrera, Albert Pujols, Harmon Killebrew … and Tony Oliva and Gil Hodges.

Oliva’s OPS+ of 131 is tied for 174th, Hodges’ 120 is tied for 390th. Allen is tied with Frank Thomas, the Hall of Famer and not the teammate who hit him with a bat (the god of analytics apparently has a delicious sense of humor), a point ahead of the guy who hit 755 home runs. (Jim Kaat’s ERA+ of 108 is tied for 411th.)

Those are discrepancies so large even Allen might not have been able to hit a homer far enough to cover them.

It’s understandable, even admirable, that the committees voted this year in a way that brought the most fans the most joy. We’re in the midst of a seemingly never-ending pandemic which has killed more than three-quarters of a million Americans; baseball has been shut down in the kind of lockout only folks with the late Gussie Busch’s mindset approve of.

We could all use a pick-me-up, and the election of some of next year’s inductees does exactly that. Unfortunately, no matter how good the votes made fans feel, a class without Dick Allen doesn’t smell so good.

Pingback: Hall of Fame ballot 2022, and who should get in | once upon a .406