I spent much of the summer of 1969 watching the Phillies play at Connie Mack Stadium, even though neither the team nor the stadium was in very good shape.

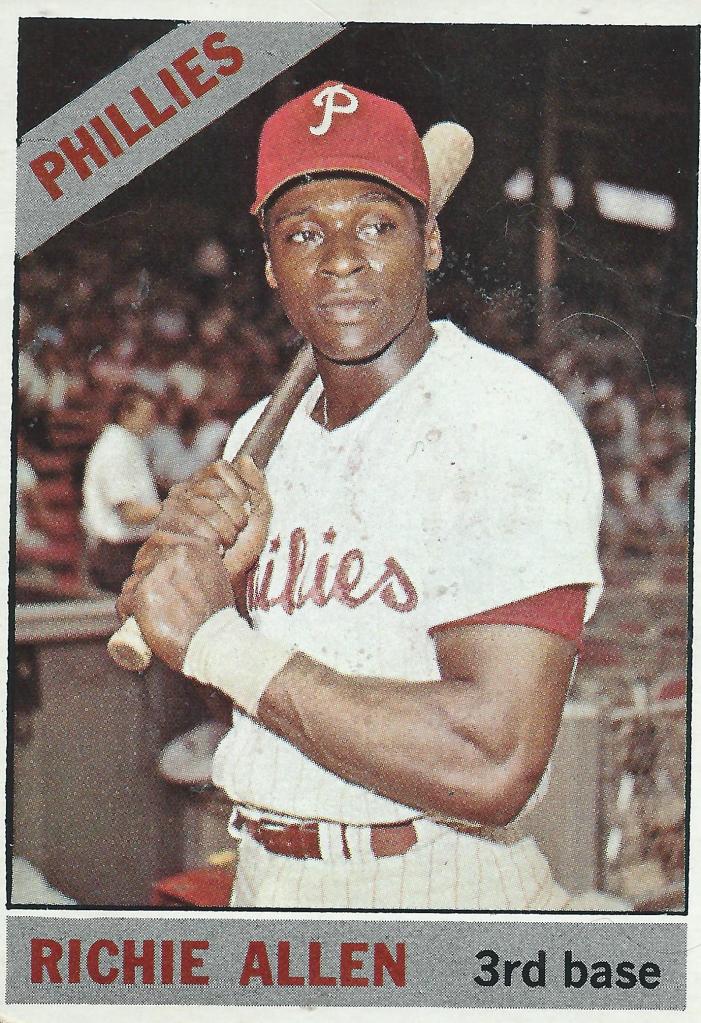

I was too young to work and too old, I thought, for overnight camp, and too bored to sit by the pool, just constructed in the backyard. Maybe there was something empowering, if not in navigating the subway, then watching a bad baseball team careen toward 100 losses. Or maybe I was bored and Dick Allen at-bats were as exciting as it got.

When people ask where were you when man first landed on the moon on July 20, 1969, I have no trouble remembering. At Connie Mack Stadium. Watching the Phillies lose. Twice. One of 12,393 misguided souls. Apollo 11 was still on the moon when I got home. (For the record, the Phillies scored one run in 18 innings and lost a doubleheader to the Cubs.)

There were signs of neglect all around that 1969 Phillies team, which finally collapsed under the weight of trying to make up for the pennant it didn’t win in 1964. For years the Phillies traded away young talent — Ferguson Jenkins, Alex Johnson, Adolfo Phillips, Danny Cater, Rudy May, Darold Knowles. By 1969 they were left with a team of 1964 holdovers (Tony Taylor, Johnny Callison, Cookie Rojas), young hopefuls (Larry Hisle, Don Money, Grant Jackson), decent veterans (Deron Johnson, Woodie Fryman), incapable veterans, overpromoted minor leaguers and Dick Allen.

What lured someone to Connie Mack that summer was Dick Allen. Would he hit a prodigious homer? Would he strike out three times, the boos increasing in volume with each? Would he trace a cry for help in the dirt? What would it say? What did it mean? How would the fans react if he did?

Allen wore a helmet in the field to protect himself from objects thrown by angry fans, played in the dirt and 32 times — 21 at home — he homered. It was bizarre baseball theater, a Twilight Zone episode built on a superstar player and the fans who excoriated him.

Allen knocked in 89 runs, scored 79 and had a .949 OPS that ranked fifth in the National League. And he was roundly booed for sport by a primarily white fan base at a stadium in a Black neighborhood. Catcher Mike Ryan batted .204, slugged .332 and had a .588 OPS and 65 OPS+. And was generally cheered. Go figure.

The Phillies lost 99 games, and many fans focused their venom on Allen, the culmination of six years of abuse.

There was something perverse and cruel and racial in the booing. Jeering a replacement Santa Claus in 1968 was a gag, a joke the national media told over and over and over until it was as tiresome as a stale and oft-repeated punch line. It’s ironic that’s the booing that tarnished Philadelphia’s reputation. Booing Allen, even as a rookie in 1964, was the travesty that should have done so.

Allen hit those 32 homers in 1969 in 118 games, because he was suspended in June after he stopped at the track in Monmouth, N.J. to watch his horse race on his way to a twi-night doubleheader at Shea Stadium. Unbeknownst to Allen, according to his bio at sabr.org, the games were moved up an hour. He got stuck in traffic and heard on the radio, according to sabr.org, that he had been suspended by manager Bob Skinner.

Allen turned the car around, headed home and wasn’t heard from for nearly a month, even as the Phillies fined him and maintained the suspension.

(Allen was still suspended the day man landed on the moon and the Phillies lost two to the Cubs. But it was also the day Allen agreed to return, causing teammate Cookie Rojas to say: “This must be the greatest day in history. The astronauts come down on the moon and Richie Allen comes down to earth.”)

Fifty years after that memorable baseball summer, I attended a Phillies game with an old friend, who still keeps score and has saved every scorecard from the nearly 2,000 games he’s attended.

I wish I had done the same, if only to note how many of Allen’s 351 career home runs I saw a half-century earlier.

Allen hit home runs on and over the roof in left field at Connie Mack (Coke was one of the words he wrote in the dirt with his cleats in 1969, for the Coke sign on the roof his batted balls seemed to take aim at). He hit them over the scoreboard in right field, and even over the fence in center field between the stands and flagpole. Center field in Connie Mack Stadium was then 447 feet away.

Listen to Phillies fans of a certain age and it’s a sure bet they have a tale of a memorable Allen home run to tell (I can recall one to the roof in left not so much for where it landed, but the awed reaction of the nearby adult fans. They wouldn’t have been more shocked if the ball disintegrated on its way and littered the stands with dollar bills).

“Now I know why they boo Richie all the time,” Pittsburgh’s Willie Stargell once said. “When he hits a home run, there’s no souvenir.”

But Allen’s story, like so many in America, was often about race. He debuted in the major leagues 16 years after Jackie Robinson did and seven years after Robinson retired, six years after the Phillies, finally, belatedly and half-heartedly became the last team in the National League to integrate.

So much had changed since Robinson debuted, and so little. The country hasn’t come to terms with race now in 400 years; baseball and its fandom certainly hadn’t done so in 16.

Allen was a young, gifted African-American athlete who didn’t conform to the expectations of white ownership, white media and white fandom. So ownership fined and suspended him, media disrespected him and called him Richie instead of Dick and fans booed him.

“One day people will understand that standing up for yourself and your dignity makes you a man and not a malcontent,” tweeted Mitchell Nathanson, author of God Almighty Hisself: The Life and Legacy of Dick Allen, after Allen died on Monday.

Baseball has ample unwritten rules which have to be abided by. But when it came to Allen, the Phillies couldn’t be bothered to remember the golden rule.

They sent him to Little Rock at age 21, to desegregate the sport there, either unknowing or uncaring. Six years earlier, it took the National Guard to desegregate the schools in Little Rock; Allen was armed only with his talent.

Not only did they send Allen without forewarning to Little Rock, they played him in the outfield. A year later, as a rookie in the majors, they moved him to third base, a position he had never played in 482 minor-league games. Unpreparedness was apparently a Phillie trademark of the era. Allen made 41 errors there for the Phillies in 1964, and the booing started.

From joeposnanski.com: “‘There are many in our fair city who pose as baseball fans,’ a William J. Kafin wrote to the Inquirer. ‘They are imposters. They boo Richie Allen. This is comparable to the French booing Joan of Arc.'”

Phillies fans might have booed Joan of Arc, too, if she made that many errors. But there was more to it. Racial unrest erupted in late August 1964 in neighborhoods not far from the ballpark, and Allen was a convenient target for white fans angered and threatened by the idea of Black equality.

From Nathanson’s book: “Although he quite obviously played no role in the riot himself and had been up to that point silent when it came to the city’s racial politics and dynamics, Dick Allen, through the color of his skin and the way he spoke his mind, had become the symbolic face that unleashed white anxiety and discontent with the changing complexion of the city in the wake of the riot.”

Who’s to say what the Phillies might have done to deter the booing, but they did in 1964 what they had so often done when it came to race — as little as possible. Allen, 22, would have to pretty much fend for himself.

(The Phillies had a general manager who told Branch Rickey, “You just can’t bring the n****r in here,” when Jackie Robinson played for the first time in Philadelphia in 1947, a manager who viciously taunted Robinson when he did, and such a lack of commitment to integration that John Kennedy, their first African-American player, appeared in five games in 1957 before he was sent to the minors, never to return. “I would not say they made a huge commitment to the development of John Kennedy,” Chris Threston, author of The Integration of Baseball in Philadelphia, told the website Billy.Penn.com. “They just wanted to get it over with.'” For the record, the aforementioned GM, Herb Pennock, is in the Hall of Fame. Allen is not.)

Allen gave the Phillies one of the great rookie seasons ever in baseball — he batted .318, slugged .557, scored 125 runs and drove in 91, led the league in triples with 13, had 80 extra-base hits and even sacrificed six times. And fans booed.

From joeposnanski.com: “‘I’m confused,’ his manager, Gene Mauch, told reporters. ‘I just don’t understand it. I guess when people have exceptional talent, they are expected to be exceptional every minute of the day. And the perfect player hasn’t been born yet.'”

The Phillies blew the pennant when they lost 10 games in a row with 12 to play, through no fault of Allen’s. He batted .414 in the 10-game losing streak, hit safely in nine of the 10 games, and had six extra-base hits, including a two-out, game-tying, 10th-inning inside-the-park home run in loss number five.

We’re left to wonder what difference, if any, it might have made had the Phillies won that pennant and perhaps delivered the team’s first World Series title.

Embittered, the fans’ booing escalated the next year after his fight with Frank Thomas. The Phillies silenced Allen and cut Thomas, because as Thomas said manager Gene Mauch told him, according to a 2015 Philadelphia Inquirer story on the fight, “You’re 35 and he’s 23.'”

Mauch might have told Thomas that he was in the wrong, and that his racist insults weren’t acceptable. But locker room humor in 1965 and boys being boys.

Asked his version of events, Thomas came off as the good guy, even though he had struck Allen with a bat. Allen was mum, and who wouldn’t resent not being allowed to defend oneself?

After that, Allen’s relationship with the fans and team deteriorated. And Allen rebelled — he missed games, he missed flights, he drank, he was tardy — the only way he could. But Allen went on hitting homers and being booed.

For a decade of a pitchers’ era, Allen was just about the best hitter in baseball. He hit 319 home runs in the 11 seasons from 1964-74, and according to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette’s Jason Mackey, only four players, all in the Hall of Fame — Hank Aaron, Harmon Killebrew, Stargell and Willie McCovey — hit more. According to Mackey, Allen had a .940 OPS in that span, second only to Aaron by a scant point.

Allen led the NL, at various times for the Phillies, in runs, triples, total bases, slugging percentage, on-base percentage, OPS and OPS+. And — cue the booing — strikeouts and errors. (He led the AL for the White Sox twice in home runs and once in RBIs and walks.)

He played third base, first base and left field — he once said he would play anywhere but in Philadelphia — after he tore tendons and severed a nerve in his right hand after pushing it through the headlight of his car. Allen could barely throw, but Mauch put him in left and had his shortstop venture as far as necessary into the outfield for relays. Allen played in 152 games in 1968 and hit 33 homers in the Year of the Pitcher with one good hand and one not-so-good hand.

That didn’t save Mauch’s job. The manager who had a simple approach to Allen — “play him, fine him, play him again” — was fired 54 games into the season.

The Phillies and their fans cited every instance of Allen’s misbehavior and ignored every provocation. They acknowledged the talent, but ignored the hard work Allen put in to hone it. Los Angeles sports writer Ross Newhan and Bruce Tanner, son of White Sox manager Chuck, said after Allen’s death they would see him in the batting cages in the early morning.

“I believe God Almighty hisself would have trouble handling Richie Allen,” George Myatt, Allen’s final manager in Philadelphia, said, unaware to the end he was going about it all wrong. From josposnanski.com: “‘Don’t talk to me about being handled,’ Allen hisself said. ‘You know what Wilt (Chamberlain) said about that: ‘Animals are handled. Not men.'”

Even Allen’s departure from Philadelphia was not without controversy. He wrote Oct. 2 in the dirt that summer of 1969, to signify the last day of the season. (He also wrote, among other things, Mom and Boo, and their messages were less clear.) Five days later, Allen was traded to St. Louis, and of the seven players in the deal, only one of them balked. It wasn’t Allen.

Curt Flood refused to report and sued baseball, beginning the legal efforts that brought about free agency. Flood, from his book The Way It Is: “Philadelphia. The nation’s northernmost southern city. Scene of Richie Allen’s ordeals. … I did not want to succeed Richie Allen in the affections of that organization, its press and its catcalling, missile-hurling audience.”

Imagine someone who played in St. Louis preferring to stay there because he thought another city was more racist.

Allen played for the Cardinals, who traded him to the Dodgers, who traded him to the White Sox. From 1969-1972, Allen played for four teams in four seasons, despite averaging nearly 32 homers a season. The vagabond nature of his career contributed to the negative image the press, and George Myatt, harped on.

From the Sporting News in 1975, via Tyler Kepner’s story in the New York Times on Wednesday: “In 12 years in the major leagues, Dick Allen never played with a pennant-winning club, which may be a measure of the man’s contribution to team success in face of his own personal achievements. There is no question about Allen’s talents as a hitter, but he is first and foremost an individualist who willfully refuses to go along with the rules that govern the rest of his teammates. Spring training? Allen scarcely needs it. Batting practice? It’s a useless waste of time for Allen. If the rest of the players are required to show up two hours before game time, 10 minutes is enough for Allen.”

I wonder if the Sporting News ever editorialized similarly about Ted Williams, a great player who won one pennant in 19 seasons, an individualist who was booed by fans, spat back at them, was fined, said he would do it again, blamed the writers and spent large parts of his career feuding with both. Allen had to barter to pry every dollar from the Phillies; Williams was eagerly compensated by an owner who delighted in spoiling him.

And, yet, Allen’s teammates disputed the image The Sporting News imagined. Jim Bunning, conservative even by baseball’s standards as he proved in his 24 years in the U.S. Congress, argued Allen’s case for the Hall of Fame in 2015 on the Golden Era Committee.

“We talked about ’64,” Bunning said, after Allen was denied the Hall of Fame by one vote, to Stan Hochman in a story at Inquirer.com. “… He’d gotten a bad rap as a third baseman. I talked about a play he made in the perfect game. To his left. Second toughest play of the game, behind the one Tony Taylor made.

“Someone said he hit 20 home runs that traveled more than 500 feet. No one, no one in baseball had ever hit that many homers that went 500 feet.”

Count Bunning as a yes on Allen for the Hall and Allen as a good teammate.

And Larry Bowa, Allen’s teammate from a decade later, defended him, too. Allen’s second act with the Phillies in 1975-76 was awkward. Allen, fans and the organization all sought absolution, but it ended sourly when Allen loyally stood up for Taylor, left off the playoff roster, and Allen committed a tough error in the NLCS. The Phillies were swept, and Allen played one more season in Oakland.

Bowa, in a statement released by the Phillies on Monday: “We had read all the stuff about how he wasn’t a good guy, but we never saw any of that. Dick was a great teammate and a great tutor for us. He couldn’t have been more open with us as young players and was actually the complete opposite of everything we had read.”

Hall of Fame voters, unfortunately, saw Allen as the Sporting News did. He got 3.7% of the vote in 1983, got knocked off the ballot for a year, got reinstated and never received more than 18.9%. And somewhere in there Bill James wrote that Allen “did more to keep his teams from winning than anyone else who ever played major league baseball,” and that Allen was “the second most controversial player in baseball history.” Number one was Rogers Hornsby, safely in the Hall.

James’ writings and Allen’s Hall results aren’t related. Voters of the era were more likely to be resistant to James’ opinions than responsive, and the second opinion was published in 2001, four years after Allen’s last appearance on the ballot.

Dick Allen was a lot to comprehend as a 13-year-old who had just mastered the Broad Street subway line. A half century later, even better understanding the racism that permeated through the sport he played, the city he played in and the team he played for, he still is.

But for young fans in the ’60s, Allen was “preternaturally cool,” as the Philadelphia Inquirer’s Frank Fitzgerald wrote on Thursday. Landing with the White Sox in 1972, he seemed even cooler, with his wide sideburns, and the cigarette that hung from his mouth as he juggled three balls on a 1972 cover of Sports Illustrated. And when Allen rebelled, it only endeared him more to young fans doing the same, or so they thought, to the authority figures in their lives.

It might be hard to explain to younger generations how alluring Allen was. It’s like trying to convince them that Joe Namath, the guy pitching Medicare on TV commercials in 2020, was once the hippest guy on the planet.

“I was labeled an outlaw, and after a while that’s what I became,’’ Allen said in his 1989 book with Tim Whitaker Crash: The Life and Times of Dick Allen.

Allen wasn’t wrong. The Phillies weren’t much into nurturing then. But organizations can change. The Red Sox were the last MLB team to integrate in 1959; 59 years later they won the 2018 World Series with an African-American MVP (Mookie Betts), an African-American ALCS MVP (Jackie Bradley Jr.) and an African-American pitcher who should have been World Series MVP (David Price).

The Phillies today aren’t the organization Allen played for in the ’60s. They retired Allen’s number three months ago at Citizens Bank Park before a mostly empty ballpark. Owner John Middleton pushed for the retirement because he said, “One of my strongest memories is a group of white suburban 8-, 9-, 10-year-old kids playing pickup ball and fantasizing about Dick Allen. … We wanted to be just like Dick.”

Middleton, who grew up in the ’60s, broke precedent for the team to retire Allen’s number. It had previously only retired the numbers of Hall of Famers. That seems fitting if only because Allen, who broke precedent once or twice himself, is a Hall of Famer in everything but name.