Editor’s note: This is the last in a series of articles retelling the 1964 season.

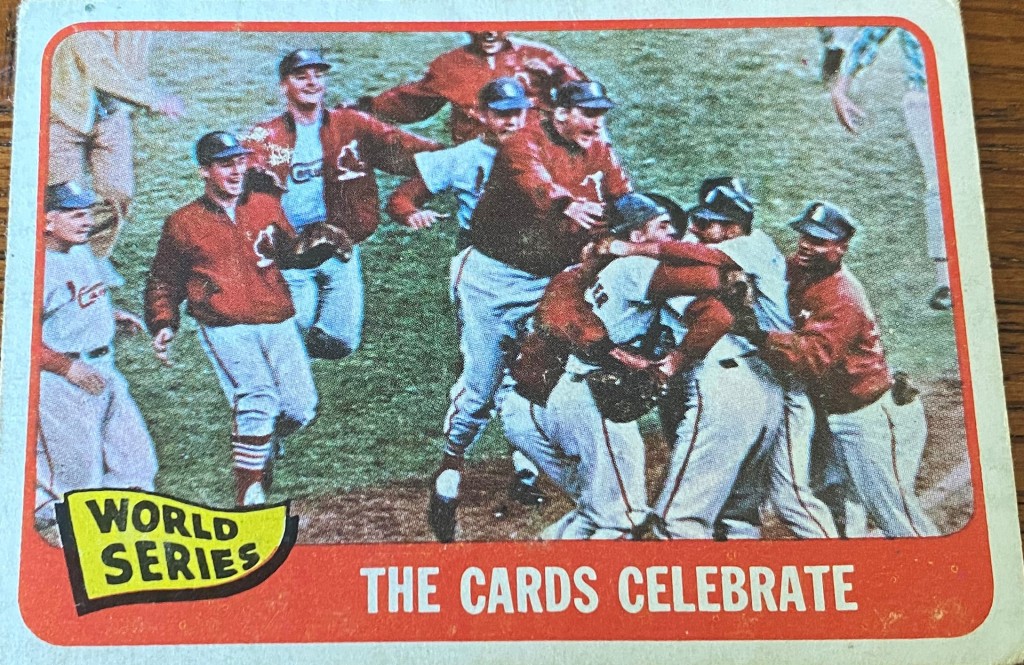

The St. Louis Cardinals won the 1964 World Series, the Yankees lost it, and the Phillies watched, probably with a little envy and a lot of melancholy.

Phillies and Phillies fans seeing the players in uniforms with red celebrating a seven-game 1964 World Series triumph surely thought the red should have been pinstriped and not a bird on a bat.

We’ll never know what might have happened had the Phillies not collapsed, or collapsed a little less, or survived it to win a playoff. But 2020 has alternative facts that 1964 didn’t.

So maybe it’s time to create an alternative reality, and an alternative World Series for 1964 to the one the Cardinals won. Maybe, just maybe, here’s what might have happened had the Phillies played the Yankees in the 1964 World Series.

Game 1: Connie Mack Stadium is all dressed up for the first time in 14 years with the World Series bunting and it looks as out of place as ties and hats do on fans at the ballpark 56 years later. It’s 55 years since Connie Mack Stadium opened as Shibe Park, and it’s hosting its 10th World Series, but just its third with the Phillies and first since the name was changed. Eddie Sawyer, manager of the 1950 Whiz Kids Phillies, throws out the first ball. “Hope you do better than I did,” Sawyer, whose Whiz Kids were swept by the Yankees, tells Gene Mauch. The national media decides the Yankees are favored, but if there’s a way for the Phillies to win, manager Gene Mauch will find it. They give Mauch the edge, between the two under 40-managers, over the Yankees’ Yogi Berra. Mauch agrees. “Yogi was too good a player to appreciate the sacrifice bunt,” says Mauch, noting Berra sacrificed just nine times in a 19-season career. Mauch says Berra would have bunted that much in a season for the Phillies, whose 97 sacrifices were second-most in the majors. Berra says he’s glad he didn’t play for Mauch. Sure enough, Cookie Rojas singles in the bottom of the first inning, MVP candidate Johnny Callison sacrifices him to second, Dick Allen walks and rookie Alex Johnson homers off Whitey Ford, 14 years his senior, to stake the Phillies to a 3-0 first-inning lead. “Sometimes you play for one run, and you get a big inning,” Mauch says. Chris Short, on short rest, pitches into the eighth inning and Jack Baldschun takes it from there. Sawyer, who resigned in 1960 after Opening Day before Mauch was hired, congratulates his successor in the locker room. “Quit while you’re ahead,” Sawyer says. “I did. Technically I was behind, but …” Berra declares Game 2 a must-win for the Yankees. “It gets late in a series early if you’re down 2-0,” he says. Phillies 8, Yankees 3

Game 2: Jim Konstanty, 1950 Whiz Kids MVP, throws out the first ball, and it’s a strike. Mauch offers him Ray Culp’s place on the roster. The Phillies could have used Konstanty. Sore-shouldered Dennis Bennett pitches gamely as Jim Bunning gets an extra day of rest after winning the deciding playoff game. Bennett trails 4-0 when he exits for a pinch-hitter in the seventh. The bullpen gives up four more in the ninth and the Yankees even the series. Allen’s late homer for the Phillies’ only run is greeted by a smattering of boos. “Should have used Konstanty,” jokes one of the writers after the game. Mauch, sharing a mood with the fans, scowls. Yankees 8, Phillies 1

Game 3: At Yankee Stadium, the Series bunting looks natural, like the difference in a man who wears a suit and tie daily versus one who wears it only for special occasions. It’s the 29th World Series for the Yankees, who’ve won 20, and the 27th at the Stadium. Bunning, having won 20 games now in each league with the help of the playoff pennant-clincher, duels with Jim Bouton. The game is taut and tense and worthy of another JB — Jim Beam. It’s tied 1-1 into the ninth when Mickey Mantle hits his record-breaking 16th Series homer to win it. How do the novice Phillies expect to win a World Series against a team whose players are breaking records set by Babe Ruth? Philadelphia sports writers warn national writers to expect the post-game buffet to be on the floor. “You should have seen what he did last year when a Little Leaguer (Joe Morgan) beat them,” one of them tells the national writers. Instead the buffet is upright and all is calm when the writers enter. “I have an amazing ability to forget,” Mauch says. “What home run? What losing streak?” Yankees 2, Phillies 1

Game 4: The Phillies’ situation appears as bleak as it did anytime in the 10-game losing streak when Art Mahaffey starts, can’t retire a batter and is pulled after facing four of them. The Yankees lead, 3-0. “Mauch hates pitchers,” Mahaffey says. “Only pitchers who can’t get outs,” Mauch retorts. Mauch turns to the appropriately named John Boozer, who holds the Yankees off into the sixth. Danny Cater’s pinch-single starts the inning and Allen’s grand-slam homer climaxes it, turning a 3-0 Yankees lead to a 4-3 Phillies advantage. Baldschun pitches the final three innings and the Phillies even the series, 2-2. The Game 4 win makes the Phillies the most successful team in franchise history. In their two previous World Series appearances, the Phillies had won one game, losing in five in 1915 to the Red Sox and being swept by the Yankees 35 years later. For comparison’s sake, the Yankees Game 3 Series win is their 98th. They can reach 100 if they win the Series. Phillies 4, Yankees 3

Game 5: Short protects a 2-0 lead into the eighth inning, when Tom Tresh ties it with a two-out homer after a Bobby Wine error. In the bottom of the ninth, Phil Linz reaches but is out trying to steal home with Roger Maris at bat. Catcher Clay Dalrymple told pitchers after Willie Davis had stolen home on Sept. 19 in the 16th inning to “throw the ball over the middle,” according to sabr.org, but Mahaffey’s pitch as Chico Ruiz stole home two nights later was hurried and wild. Short calmly throws a strike in Game 5 and Maris is as surprised as Berra. Dalrymple tags Linz out, and Mauch is triumphant. “Put that in your harmonica and play it,” he crows from the Phillies dugout. Dalrymple homers with two on in the top of the 10th and the Phillies take a 3-2 Series lead. Asked about the Phillies being a win away, Berra says, “It’s like deja vu all over again.” Even Mauch isn’t sure whether the opposing manager is one step ahead of him or two steps behind. Phillies 5, Yankees 2

Game 6: Shortstop Dave Bancroft, one of the last surviving members of the Phillies’ 1915 pennant winners, throws out the first ball. “I like the way you played,” Mauch tells him, after consulting the Baseball Encylcopedia and learning Bancroft sacrificed 23 times in 1915 and 212 times in his career. Mauch opts to hold Bunning for a Game 7 if he needs him and sends a game Bennett out one more time. “Great,” snorts one Philly sportswriter in the press box. “He almost cost them the pennant by starting pitchers with too little rest; now he’s going to blow the World Series by giving his starters too much rest.” It doesn’t go well. Mantle homers, Maris homers and the Yankees build a big lead early. Mauch, upon hearing Bouton is an avid reader, tries to rattle the Yankees starter. “Why don’t you read a book, you egghead,” he yells out at Bouton. Unperturbed, Bouton yells back, “Better yet, I’ll write one Gene. And you won’t be in it,” and goes on to complete a six-hitter. Flustered, Mauch takes his ire out on Yankees first baseman Joe Pepitone. When Pepitone comes near the Phillies dugout in pursuit of a pop up in the seventh inning, he gets a shove from Mauch and falls awkwardly. The melodramatic Pepitone is uninjured except for a sore butt, but he leaves only on a stretcher and after two ovations. Asked if Pepitone will be ready for Game 7, Berra sneers. “He fell on his ass. There’s a better chance he’ll do something tonight that will keep him from playing tomorrow.” Yankees 7, Phillies 2

Game 7: The day of the deciding game, with Mel Stottlemyre on two days rest to pitch against Bunning on four, dawns partly cloudy. A wag in the press box wonders if Mauch will lobby to have it postponed, as he did in August when the Phillies were to face Sandy Koufax. “He’s got reason to be afraid of pitchers on two days rest,” the wag says. Lefty O’Doul, who batted .398 for the 1929 Phillies and .383 for the 1930 Phillies, throws out the first ball. The choice of O’Doul, whose 1930 Phillies finished last and lost 102 games, is second-guessed in the press box every bit as avidly as Mauch’s handling of the pitching staff. A member of the Phillies PR staff shrugs. “There are only two pennant winners in our history,” one of them says, “and almost everyone else from 1915 is unavailable because they’re dead.” But there’s no bad karma from the 1930 Phillies on this day. Bunning is dominant until the ninth, and by then it’s too late for the Yankees. Callison and Allen homer, the latter’s third of the Series, and when Cookie Rojas doubles in two in the seventh, even Berra has to admit it was over before it was over. Allen is named MVP of the Series, and in the raucous Phillies locker room, Mauch declares, “This town will love him like I do. Forever.” Bunning is toasted and asked what he’s going to do after his playing career is over. After all, he has nine children to support. “Maybe run for Congress. Support labor,” says Bunning, the Phillies player representative. “Stand up for the little guy.” Callison, overhearing, guffaws. “The only little guy you’ll ever stand up for is Bobby Shantz,” he says, referring to the Phillies’ 5-foot-6 reliever. Mauch is asked if his style of managing will change the game. “I’m not the manager because I’m always right,” he says, “but I’m always right because I’m the manager.” Berra enters the Phillies locker room to offer congratulations. “We made too many wrong mistakes,” Berra says. “In baseball, you don’t know nothing.” And Mauch, humbled by victory at last, agrees. Phillies 9, Yankees 2